A faculty–alumni partnership shows how Belmont prepares architects to think critically, design ethically and shape the profession beyond the studio

When Emily Schiedemeyer first worked on a community-focused design studio as a Belmont University architecture student, she saw it as an ambitious academic project — one that demanded collaboration, creativity and thoughtful consideration of how people live. That same work has taken on new life for her post-grad, offering proof of how Belmont’s approach to architectural education extends well beyond graduation.

When Emily Schiedemeyer first worked on a community-focused design studio as a Belmont University architecture student, she saw it as an ambitious academic project — one that demanded collaboration, creativity and thoughtful consideration of how people live. That same work has taken on new life for her post-grad, offering proof of how Belmont’s approach to architectural education extends well beyond graduation.

Schiedemeyer, now an architect at ESa, is one of three Belmont architecture alumni whose undergraduate studio project became the foundation for a recent peer-reviewed research article led by Dr. Fernando Lima, chair of the architecture department and an assistant professor in Belmont’s O’More College of Architecture & Design. The collaboration also included alumni Anna Agnew and Vira Williams.

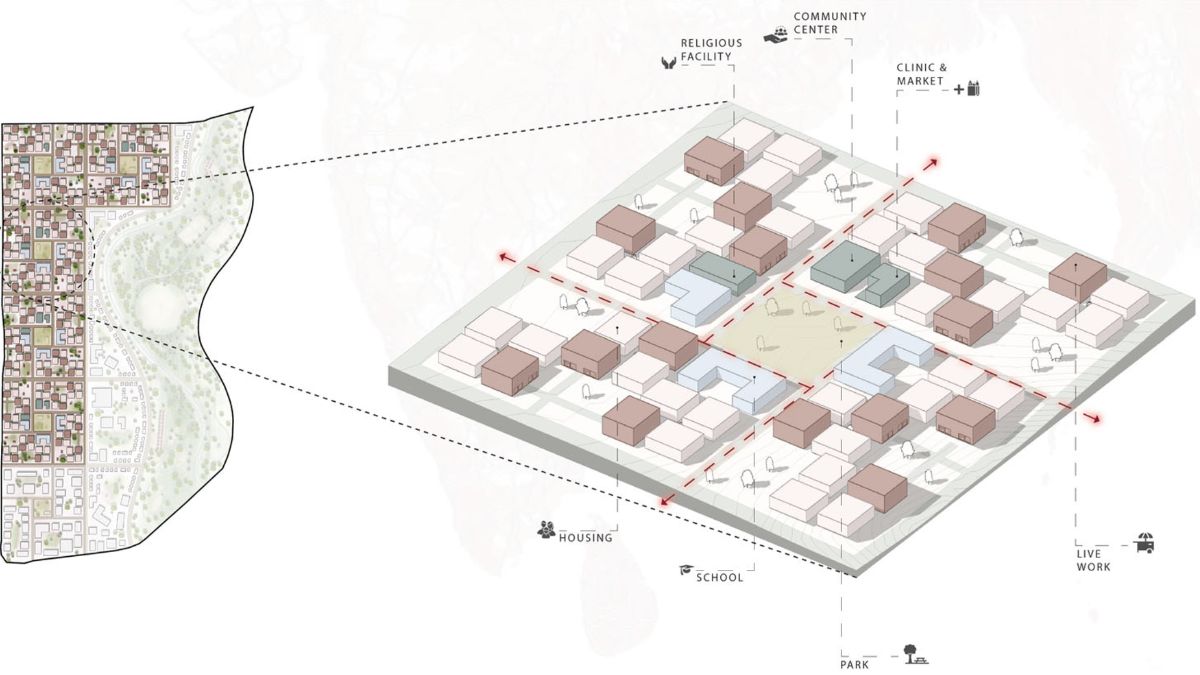

The article, titled “Computational Design and Service Learning in Informal Settlement Planning: A Pedagogical Model for Architectural Education," examines how architecture students can use advanced computational tools to respond more thoughtfully to real communities. Drawing directly from the alumni’s undergraduate studio work, the research shows how student observations of an informal settlement were translated into flexible, rule-based design systems. This demonstrates how technology, when paired with service learning, can support ethical, community-centered design rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

Rather than positioning the article as a traditional academic milestone, Lima sees it as something more meaningful: a reflection of how Belmont students are trained to approach real-world challenges with empathy, rigor and purpose.

“This project is all about the things we care about most here,” Lima said. “How can we promote physical transformations that enable human ones?”

From Studio Project to Professional Credibility

The original studio project asked students to study an informal settlement in Ahmedabad, India, and consider how communities grow organically — socially, spatially and culturally. Using computational design tools, students developed flexible design systems that could adapt to different family needs and community contexts, rather than proposing a single, fixed solution.

The original studio project asked students to study an informal settlement in Ahmedabad, India, and consider how communities grow organically — socially, spatially and culturally. Using computational design tools, students developed flexible design systems that could adapt to different family needs and community contexts, rather than proposing a single, fixed solution.

For Schiedemeyer, the experience stood out because of its scale and collaborative nature.

“The project was so comprehensive,” she said. “We were thinking about circulation, access, public space and overall quality of life all at once. It felt like a big academic challenge at the time, so it’s been interesting to see how our work still has relevance years later.”

That relevance has translated directly into professional credibility. According to Lima, the project has become a standout element in the alumni’s portfolios, frequently sparking conversation during interviews and career fairs.

“They are working professionals now,” Lima said. “And their critical thinking was so strong that it set them apart. Employers were excited by this work, and that tells us something important about how education connects to practice.”

Alumni as Co-Creators

What makes this collaboration distinct is the role alumni played in shaping the research narrative. Rather than serving as examples of successful graduates, Schiedemeyer and her peers were invited back as intellectual partners, helping contextualize their student work within a broader conversation about architectural education.

Revisiting the project as an alumna offered Schiedemeyer a new perspective.

“Seeing our work framed in a research context allowed me to look back with more clarity,” she said. “Instead of remembering it only through deadlines and pin-ups, I can see the strength of the ideas and how that early design thinking contributed to something larger.”

That reflective process reinforces the sustained faculty–alumni relationships that evolve over time, one of Belmont’s defining strengths. Lima notes that this continuity is intentional, rooted in a belief that education does not end at commencement.

“This is what we do here at Belmont,” he said. “We prepare students to meet professional expectations, but also to think critically, solve complex problems and engage with real-world issues using many different tools.”

Designing With Purpose

While the global context of the project helps explain its significance, the deeper takeaway lies in how Belmont students are taught to approach design itself. For Schiedemeyer, the studio reaffirmed architecture’s responsibility to the people and communities it serves.

“Even in an academic setting, we were exploring real considerations like access, safety and long-term livability,” she said. “It reminded me that thoughtful design can continue to inform conversations about community impact long after the studio ends.”

Lima hopes that prospective and current students see this story as evidence of what a Belmont education makes possible.

“We are training professionals, but we are also forming critical thinkers,” he said. “Design becomes a vehicle for change — a way to elevate people’s lives. That’s the kind of architect we want to send into the world.”

Learn More

Dive into architecture at Belmont.