Alumna returns to campus with new campus exhibition shaped by four-day darkness retreat

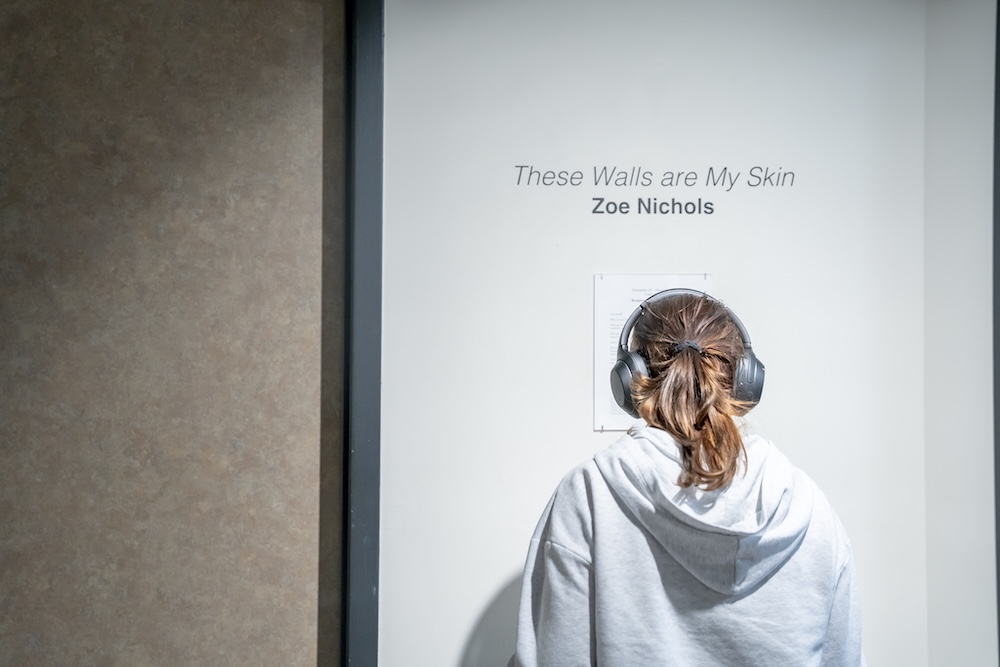

Belmont alumna Zoe Nichols (B.F.A. ’24) created a new exhibition currently on display in Belmont’s Gallery 121, “These Walls Are My Skin,” shaped by a four-day darkness retreat, months living off-grid in the Oregon woods and an ongoing fascination with what remains when something disappears.

We spoke with Zoe about her path since graduation, the themes behind her work and the Belmont mentors who continue to shape her as an artist.

You graduated from Belmont in 2024. What has your path looked like since then?

After my senior thesis exhibition — an exploration of absence and light — I received the Walter and Sara Knestrick Award. I proposed using the grant to continue my research by doing a darkness retreat. There are only a few in the world, and the one I was drawn to in Oregon had a three-year waitlist. I emailed the director nonstop and got in because someone canceled. Within 24 hours I was on a plane.

While waiting for the retreat to open up, I lived in Birmingham and had a studio in a community makerspace. But after the retreat, they offered me a seasonal job cooking for participants. So, I moved back to Oregon last May, lived completely off-grid in a yurt and developed this body of work on the land where all of this began. It was unexpected but deeply right.

Where did those themes of absence and light that you explored in your thesis exhibition originate for you?

They go back to a few core experiences. As a junior, I spent a semester in the same region of Oregon at the Belmont USA Oregon Extension program. There’s a labyrinth there that became really meaningful to me. Walking it daily, I started noticing “indexes” — marks that point to something no longer present, like a scratch in a table or a worn doorknob. That was my entry point into thinking visually about absence.

At the same time, a family member received a terminal prognosis. That made me think about what traces we leave, how absence shows up physically. And my dad is a photographer, so we grew up being taught to pay attention to light — where it hits, what it reveals, how it coats everything without being physical.

Those threads came together in my thesis, which was all about calling attention to light in the gallery space.

How did that attention to light lead you toward total darkness?

We give so much language to light. I’d spent years visually attending to it. I wondered what would happen if I took that away entirely — if the thing I loved most was removed. What surprised me was that the dark was incredibly kind. Removing light didn’t feel empty; it felt generous. That curiosity became the foundation for this new work.

What aspects of your time at Belmont/Watkins most shaped the artist you are now?

Two things: dialogue and professors who model what an active creative life looks like.

As an art studies and philosophy double major, those disciplines constantly fed each other. Andy Davis’s Philosophy of the Arts class lit my brain on fire. He introduced me to thinkers like Merleau-Ponty, who writes about the visible and invisible — ideas that echo throughout my work.

In the art building, professors like Kristi Hargrove, Thomas Sturgill and Mandy Rogers Horton were huge influences. They bring rigorous discourse into the classroom, but they’re also deeply committed, practicing artists. Those relationships have continued past graduation; they even did Zoom critiques with me while I was in Oregon. That ongoing support is something I’m really grateful for.

What advice would you give students drawn to slower, more tactile fine-art paths?

Stay in community. After graduating, I realized how much I missed the dialogue, the conversations where ideas come alive. Keeping close contact with my professors and peers has grounded me.

And embrace slowness. This work took a year and a half of thinking, writing, wandering, experimenting, failing and redirecting. Pay attention to what energizes you: materials, conversations, images, books. Following those sparks is what leads you to the next step.

Your artist talk is written almost like a poetic letter. How do writing and storytelling intertwine with your visual work?

I initially planned to give an academic talk, but the story of the darkness retreat didn’t feel like it fit inside that kind of language. The experience was strange and nonlinear, almost outside of time. Writing in a looser, more poetic voice felt more honest.

The show is also about secrets, so I wanted the writing to protect some of that hiddenness. Throughout the exhibition, I tucked pieces of the story into the labels and titles. The writing scatters clues, and the work holds the rest.

What do you hope someone experiences when they walk through your exhibition?

I hope they feel invited to pay attention. You know those little liminal moments: walking somewhere without your phone, catching a shadow or a color that excites you? I hope the show sparks that kind of noticing. There are subtle things scattered everywhere. If viewers enter with curiosity, there are secrets waiting for them.

Is there a piece in the exhibition that feels particularly central to the show?

There are two directions that feel central. One is a gesture toward the space itself: I cut out the Tolstoy quote that’s carved into the exterior wall of the art building and brought each letter through to the inside wall in mirror image. It’s a way of thinking about interior and exterior, body and shadow.

Materially, I biocharred bones and other objects — essentially turning them into charcoal through subtractive fire. Everything burns away except the carbon, so the original form is preserved as a shadow of itself. That material mirrors the themes of reduction, transformation and what remains.

And there’s a photograph called “Stone Fruit” that’s especially meaningful to me, though I prefer not to explain it. Some things feel more alive when they stay partially hidden.

What themes or pathways are calling to you next?

I’m looking at some graduate programs because I’m excited to return to structured dialogue again. Creatively, I’m also curious about end-of-life care. Right before my darkness retreat, I spent several months visiting a neighbor who was receiving hospice care and had lost her vision. Sitting with her — watching someone move through so many “lasts” — while my friends and I are in the stage of life moving through so many “firsts” was really meaningful.

I don’t know what shape that will take yet, but it feels like a quiet signal for what might be ahead.

“These Walls Are My Skin” will be on display through Dec. 5 in the Leu Center for the Visual Arts Gallery 121.

Learn More

Discover Belmont's fine arts programs